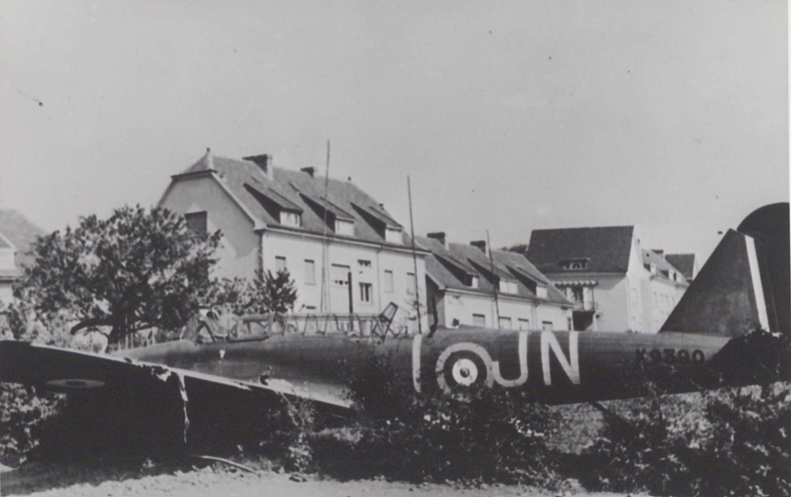

Header photo British fighter plane shot down in Merl, a suburb of Luxembourg City. © ANLux 005-01-107

Rescuing allied airmen

It is estimated that over 300 Allied aircraft, bombers and fighter planes, were shot down over Luxembourg during the war as well as several hundred over the Belgian Ardennes. The majority were part of the air campaigns carried out by the Allied forces, such as the Allied bombing campaigns and the liberation of Western Europe. This airspace was a frequent target for German anti-aircraft defences and Luftwaffe fighter planes. Many of the downed planes crashed in the forests and fields and some of the crew members survived, while others were either captured or tragically lost their lives.

Allied airmen who were successfully able to bail out and land safely were often hidden initially by local farmers or civilians before being handed over to the resistance who would continue to hide them in a network of safe houses. They could then be transported over the border and handed to the Belgian white army to be repatriated to England using proven escape routes often via France, Spain and Portugal.

Pierre Schon and his LPL compatriots helped several allied airmen to safety during this period providing them with false identities and Pierre sometimes gave them his own clothes so they could pass as civilians. Below are examples from the US archives. As of April 1943 he operated on the Belgian side of the border having had to flee the Gestapo who had issued an arrest warrant for him in Luxembourg.

In early December 1943 Pierre hid a Canadian pilot whose plane had come down in Haversein-Buissonville in the Belgian Ardennes. His name was David Smith from Winnepeg. Pierre looked after the pilot for 3 – 4 days. The pilot received civilian clothes in the Petit Café in Havrenne (Rochefort) and one of Pierre’s gabardines. Pierre passed him on to Jan Collard in Bastogne from where he left 10 days later for Brussels with Jules Dominique (renowned resistance member who had recruited Pierre).

On 4 February 1944 Aloyse Kremer handed over 3 American pilots to Pierre. Their names Joe Kerpan, Robert Korch and Donald Toye from Oregan. They were brought over the border with 40 Luxembourgers. Pierre provided them with false ID cards and gave one of them his new gabardine. According to Donald Toye, the 3 airmen took the train to Bastogne and that evening were taken to Herve by the village priest where they stayed 5 days in his house. The priest was the leader in one of the resistance groups. They received false ID cards and on 24 April they were taken to a white army forest camp, west of Morhet. Pierre confirmed the camp or maquis they were taken to was the Haversin camp run by the Belgian resistance.

In spring 1944, with the Allied invasion of France looming, the Comet Line, in consultation with MI9, decided to stop removals and instead gather airmen into forest camps (Maquis) where they could await the arrival of the Allied armies.

On 5 February 1944 an American bomber landed near Ottré Vielsalm near Bastogne Belgium. Pierre and camorades Jos Tholl and Paul Cormotte searched for the spot and found the machine gunner. They kitted him out in new clothes and handed him over to François Charlier in Hebronval where the six others from the plane were gathered. The pilots were sheltered in the Deaf and Dumb Institute in Sierneux. Unfortunately it was raided by the Gestapo and it not clear what happened to the 7 airmen afterwards.

In June 1944 Aloyse Kremer and Pierre Kergen brought over the border from Luxembourg to Limerlé in Belgium two British and one Canadian pilots. Edgar Michaud (Canadian), Alan Best (British), and Ronald Dawson (British). The pilots had been hidden beforehand on the Schon family farm. Pierre Schon provided them with false IDs and 200 francs each. Afterwards they were taken to the Maquis du Lion Rouge headed by Jules Dominique. Two continued their journey and Alan Best stayed with the maquis until the liberation.

Photo from left to right the two Kremer brothers Eugène and Aloyse (LPL) with Pierre Schon (LPL), Edgar Michaud (Canadian airman), Pierre Kergen (LPL), Ferd Hansen (refugee from Clervaux), Alan Best (British airman), Ronald Dawson (British airman), and Batty Mutsch (LPL). The group had just arrived from Luxembourg to Limerlé station in Belgium.

Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Resistance and Human rights, Luxembourg

In May 1944, Jos Racke brought Pierre a Canadian pilot. Pierre provided him with false papers and 500 francs and took him over the border to Belgium accompanied by Michel Kirtz. He was handed over to the Maquis (forest camp) where he stayed until the liberation.

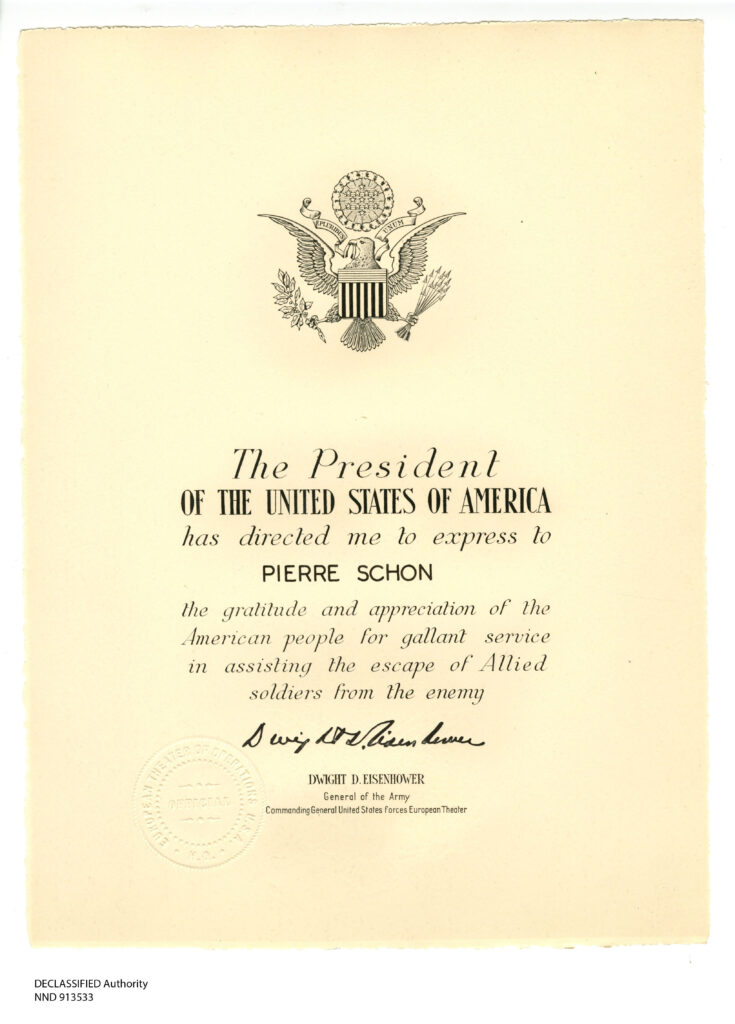

Commendations

Shortly after the war, Pierre received two commendations. One from the USA signed by General Eisenhower and one from the Commonwealth of Nations signed by the Deputy Chief Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force expressing their thanks and appreciation for assisting the escape of allied soldiers and airmen from the enemy.

The Maquis under German attack

There were approximately 20 Maquis (resistance forest camps) operating in the Belgian Ardennes in the spring and summer of 1944 and they stepped up their sabotage activities as the allied troops advanced across Europe. The camps were made up of brave Belgians and Luxembourgers, the latter who had escaped from forced conscription to the German army or were political prisoners on the run. Pierre Schon, the head of the Maquis near Lavacherie and his maquisards (resistant fighters) formed part of this active network.

These camps became more than a minor irritation for the Nazi occupiers constantly disrupting important supply lines. As soon as one railway line or major road was repaired, it would be destroyed shortly afterwards by yet another attack.

Several forest camps were discovered, stormed and dismantled after a betrayal or reconnaissance by German forces. These included Camp de Chenet, Camp d`Ebly, Camp de Genevaux, Camp de Lierneux, Camp de Mussy, and Camp de Rulles. A number of resistance members were injured or killed in the armed combat, others arrested and executed, with the few lucky ones sent to camps or prisons where they survived to welcome the liberation. More details and source Pierre Kergen (LPL resistance member).

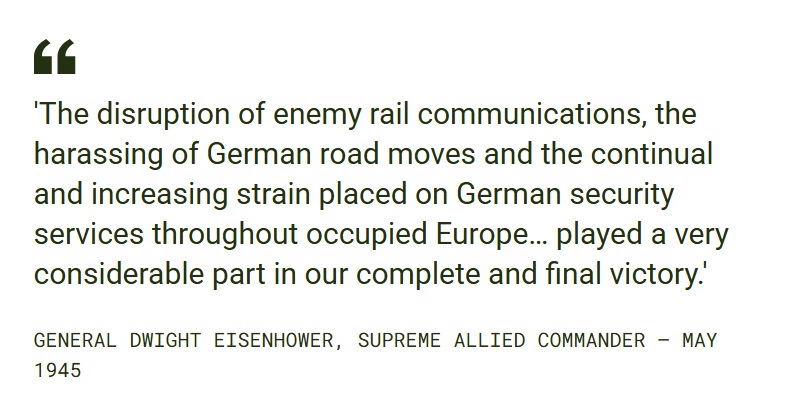

In May 1945, General Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander for Europe who spearheaded the liberation of Western Europe with the allied forces summed up the importance of the resistance movements.

The Kergen family

The Kergen family farm was located in the small village of Sassel, just 7 km from Clervaux and 9 km from Doennange, where the Schons had their own farm. In July 1941, at the age of 19, eldest son Pierre Kergen was welcomed into the LPL North resistance group by co-founder Josy Fellens. True patriots, the Kergen family maintained two hideouts on their farm and, at great personal risk, sheltered dozens and dozens of escapees between 1941 and 1944.

Like his counterpart Pierre Schon, Pierre Kergen became a seasoned escape guide, escorting more than a hundred individuals to safety across the Belgian border. Alongside his trusted comrades Eugène Kremer and Batty Mutsch, the team quickly earned a reputation for effectiveness and courage. In addition to his escape guide activities, Kergen also served as an intelligence liaison officer in a clandestine Belgo-Luxembourgish intelligence network, just as Pierre Schon did and was a member of the Belgian resistance for a short period of time.

From 1943 onward, the two Pierres collaborated closely. Schon, operating from Belgium would receive and guide escapees that Kergen and his comrades had brought across the border, continuing their journey through Belgium and into resistance camps hidden in the forests. Both men were eventually forced to flee to Belgium during the German counteroffensive and would spend the final days of 1944 together, no longer resistance operatives, but posing as ‘refugees’.

An unexpected act of reprisal

Clervaux and the surrounding villages were first liberated by U.S. forces on 10 September 1944, allowing the people of the Luxembourg Ardennes to begin enjoying their long-awaited freedom. They welcomed their American liberators with open arms, a show of gratitude that did not go unnoticed by a nearby SS unit monitoring the border village of Kalborn.

On 22 September, shrouded in early morning fog, the SS descended on the Hoelpes house, where several families were sheltering in the cellar. Frustrated by their retreat to the German border, the SS commander was determined to exact revenge on the local population. The soldiers forced the inhabitants outside and, without mercy, executed seven young men in a hail of bullets. Their bodies fell lifeless into a small pond. Among the victims were four brothers from the Hoelpes family. A fifth brother, just thirteen years old, was spared at the last moment, the SS commander deeming him too young to be shot.

The massacre sent shock waves through the region. When the Germans launched their counteroffensive on 16 December, memories of that atrocity compelled a number of young men to flee across the border into Belgium, choosing the uncertain path of a refugee over the risk of execution by the returning Nazis. The event left a lasting mark on those who survived. Pierre Schon, outraged by the tragedy, would speak for decades afterward about the senseless slaughter of those defenseless young men.

The refugee convoys to Belgium

From mid September to mid December 1944, many farms in the Oesling region hosted their American liberators, offering spare rooms, living areas, barns, and outbuildings as lodging for the troops. Pierre, who spoke English quite well, engaged in conversation with the U.S. soldiers. One thing they shared was a deep understanding of armed combat. They had and were all still facing the same enemy. The Germans launched their surprise counter offensive early in the morning of 16 December. During the night of the 16 – 17 December the Americans received radio instructions to regroup. Pierre sprang into action and left with the Americans knowing he would have to flee once again to Belgium to avoid certain death if the Nazis suddenly returned.

To help out the “C.I.C” (Counter Intelligence Corps, US Army Intelligence Agency) Pierre agreed to assist the growing number of refugees and guided convoys to safety to Belgium. The convoys were made up of civilians on foot, people with bicycles and horse drawn carriages, all scrambling to leave on the spur of the moment.

Photo © ANLux 005-01-147

Time is of the essence

The people wishing to escape gathered at agreed meeting points. Meanwhile, canon fire could be heard in the distance. This time the border to Belgium was open but for how long? The groups needed to head west and very fast.

From 16 to 18 December, although lightly equipped and outnumbered, the 110th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. 28th Infantry Division, put up a fierce defense of Clervaux, delaying the German advance and buying valuable time for Allied reinforcements to mobilise. This also gave Pierre and the Luxembourg convoys an extra valuable day to put some distance between themselves and the advancing German army.

Uncertain how quickly the Germans would advance, Pierre urged those on foot to take the train as far west as possible. Though the trains were packed, many managed to squeeze aboard the few that were still running. The group agreed to reunite later at a set point further west.

Meanwhile, those traveling by horse-drawn carts and bicycles took the main road toward Houffalize, continuing on toward La Roche, passing countless American military trucks headed to the front lines. A long procession of hundreds of refugees stretched along the road, all moving in the same direction toward safety.

The obvious destination was Marloie and the trusted network of safe houses and farms set up by Jean Boever. Here the convoys could rest for a short while, resource and the horses could be fed.

By 19 December, the German army had recaptured all of northern Luxembourg and the dreaded Gestapo returned, out to inflict maximum punishment on the local population and anyone suspected of supporting the Allies. In those long six weeks of reoccupation, over 120 people were arrested and 39 executed or deported. The local farms found their houses and barns once again occupied by German troops. The locals tried to put on a brave face and appear helpful, secretly hoping the Allies would soon return.

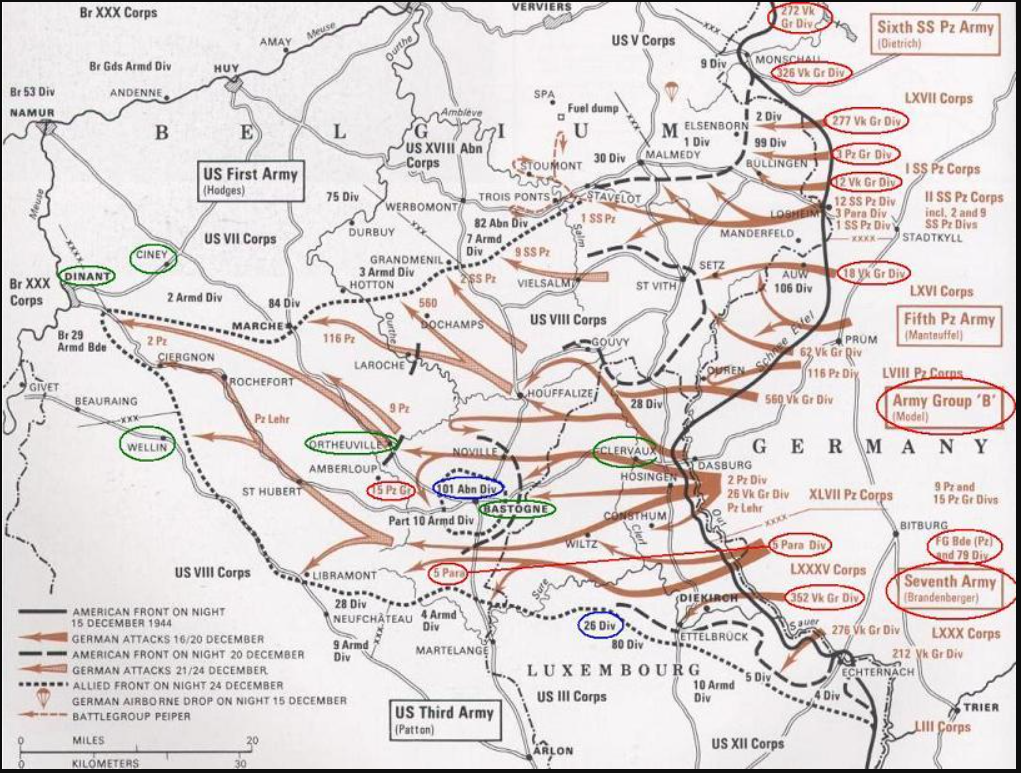

On 20 December when the Germans pushed back into Belgium and surrounded the town of Bastogne, elements of the 101st Airborne Division, reinforced by units like the 10th Armored Division, held the town under siege despite being encircled, outgunned, and short on supplies. The siege was finally broken on 26 December when General George Patton’s Third Army broke through the German lines to relieve the defenders. This is often viewed as a turning point for the Allies in the Battle of the Bulge.

Map showing the extent of the German counter offensive into Belgium – Map Padresteve

The groups had to keep moving west. By 21 December, the Germans had already reached Rochefort, west of Marloie, as the convoys made their way to Beauraing direction Dinant to reach the bridge over the Meuse river before it closed to civilians. There were just 30 kms separating Dinant and Rochefort and the advancing German army.

On the road together

The weather made an already difficult situation even more challenging. Temperatures often dropped well below freezing, and the intense cold added to the refugee hardship. On December 23, a turning point came when the persistent fog lifted, revealing clear blue skies filled with Allied aircraft. The planes were heading to support ground troops and to strike at German positions and supply lines, a critical shift in the course of the battle.

As the groups moved closer to Dinant, they encountered numerous British reinforcements advancing toward the front to push back the German forces. The sight of the Allied buildup gave the groups a renewed sense of hope.

The refugees slept on the floors of schools, farms, and even barns. Generous locals provided food, as did the refugee aid centres (centres d’accueil). The groups also had some money and bought whatever supplies they could once their own provisions ran out.

After crossing the Meuse River, the groups moved in the direction of Philippeville. On December 22 and 23, many Luxembourgers gathered at a castle near Anthée, where a large fire was burning and warm coffee awaited them. Familiar faces from home began to appear, bringing a sense of comfort and relief.

Exhausted, around 60 refugees spent the night together on the floor of a school. The building was heated, a much-welcomed comfort after days of cold and uncertainty. In the following days, the refugees began to split into smaller groups and scattered to different locations, which made it easier to find shelter. Some even offered to work on local farms in exchange for food and a place to stay.

A detailed personal day by day account of Pierre Kergen`s flight to safety can be found in his 2002 book Kriegserinnerungen eines Oeslinger Resistenzlers.

In the final days of December, Pierre Schon and Pierre Kergen, both affectionately known to family and friends as Pierchen (“little Peter”), decided to take the train to Charleroi. Their first stop was the refugee aid centre, where they presented their refugee ID cards and received food vouchers. The clerk told them the rations should last ten days. However, just a day and a half later, the two hungry men had already used them all.

That night, they slept fully clothed in the town’s hostel, which was free of charge. The next day, they ventured into the town to enjoy the lively atmosphere and the shop windows, sights they had not experienced in a long time after months spent hiding in the Ardennes forests and then returning to their small villages.

A couple of days later, the two men took the train to Brussels, where they again visited the centre d’accueil to collect more food vouchers. Although they had originally planned to continue on to the bustling city of Antwerp, they changed their minds when they learned the city was still under attack by the German V-1 pilotless flying bombs – doodlebugs – which were also raining down on and terrorizing the civilians of London.

Their visits to these cities were a much-needed distraction as both men remained deeply worried about the fate of their families, who were once again living under Nazi control in the Luxembourg Ardennes. While in Brussels, Pierre Schon used the opportunity to catch up with Alphonse Rodesch and to visit the embassy to discuss the travel authorisations needed for the Luxembourg refugees to return home. At the time, the Ardennes region was divided into several militarised zones, so travel authorisation was required.

By the end of December, news began to trickle in about the liberation of Bastogne and the Allied forces’ pushback of the Germans. This gave both men a renewed sense of hope, and they began to believe that in a few weeks, they might finally be able to start planning their journey back home.

Return home

In the last week of January, many of the refugees began their journey back home to Luxembourg. As they traveled, they were shocked by the sheer devastation they encountered in the Ardennes towns like La Roche and Houffalize, which had borne the brunt of intense fighting and heavy bombardments. These were places they had not known had been at the heart of such fierce combat. As they continued their journey, they wondered what they would find awaiting them, back home in the Luxembourg Ardennes. Pierre finally reached the family farm on 1 February 1945. What an eventful 6 weeks it had been.

Several houses on the outskirts of Doennange had been destroyed by artillery fire. Twelve dead horses were strewn in a field overlooking the village. Pierre helped bury them. An American artillery gun was positioned on the hill just above the farm. Heavy fighting and devastation had ravaged the nearby towns of Wiltz, Clervaux, Troisvierges, Ettelbruck, and Diekirch.

When Germany launched its counteroffensive, Nic, Pierre’s older brother, quickly harnessed the horse and carriage to join the convoys fleeing to Belgium. Still shaken by his recent arrest and interrogation by the Gestapo, he sought safety for himself, his wife Albertine, their four-year-old daughter Clothilde, and their three-month-old baby Ferdinand. With snow blanketing the roads and Ferdinand showing signs of a lung infection, the journey was risky. A kind Belgian farmer near Gouvy took them in. Tragically, Ferdinand died two weeks later, at a time when antibiotics were not widely available, especially not in war torn Europe. He was buried in a small coffin at the edge of the local cemetery, until it was safe to return to Doennange and lay him to rest in the family grave.

SS Rampage

The atrocities by the German SS continued into spring 1945.

On Christmas Eve, December 24, 1944, in reprisal for local resistance actions months earlier – specifically a September attack by Belgian maquis members that killed three German soldiers – 34 civilians from the village of Bande were executed by the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the SS’s intelligence and security branch. As German forces reoccupied the area during the Ardennes Offensive, the victims were rounded up, taken to a cellar along the N4 road, and systematically shot. Their bodies were left hidden at the site.

One man, Léon Praile, managed to escape the execution by fleeing into the woods, making him the sole survivor. Upon liberation by British forces on 10 January 1945, the bodies were discovered by a joint Belgian and Canadian military team and later reburied in a collective funeral held on 18 January 1945. Bande was one of the regions where Pierre Schon and his maquis had been active.

The Sonnenburg Massacre (now Słońsk, Poland) occurred on the night of 30 – 31 January 1945, just days before Soviet forces arrived. As the Red Army advanced, Nazi SS troops executed 819 prisoners held in the Sonnenburg prison, including 91 young Luxembourgers who had been forcibly conscripted into the German army and imprisoned for resisting or deserting. Other prisoners included French, Dutch, Belgian, Polish, Russian, and Yugoslav.

The SS carried out the massacre as a final act of repression against those who had resisted Nazi authority. The mass execution was also intended to eliminate witnesses and suppress resistance. The prisoners were shot in the prison yard, and their bodies were left there until the Soviets liberated the site two days later on 2 February 1945, finding only four survivors.

The massacre is one of the most tragic events in Luxembourg’s history and is commemorated annually in both Luxembourg and Poland to honour the victims with ceremonies, including wreath-laying at monuments in both Luxembourg city and Slonsk.

War is brutal and unrelenting. The devastation ensures there are no true winners, only survivors. As these two cases prove, in the shadow of oppression, the yearning for freedom eclipses all else but the human cost is immeasurable.

Eternal gratitude

In 1998, Don Toye from Oregon, one of the American airmen shot down over Luxembourg in 1944, returned to meet the surviving members of the LPL North resistance group who had helped him evade capture 54 years earlier. Though decades had passed, the immense gratitude remained undiminished and still endures today. Deepest thanks to the American and Commonwealth liberators, and profound, everlasting respect to the well over one hundred thousand brave Allied soldiers who gave their lives to free Western Europe from Nazi oppression. So that we may enjoy the freedom we often take for granted, simply because it is all we have ever known.

Gallery

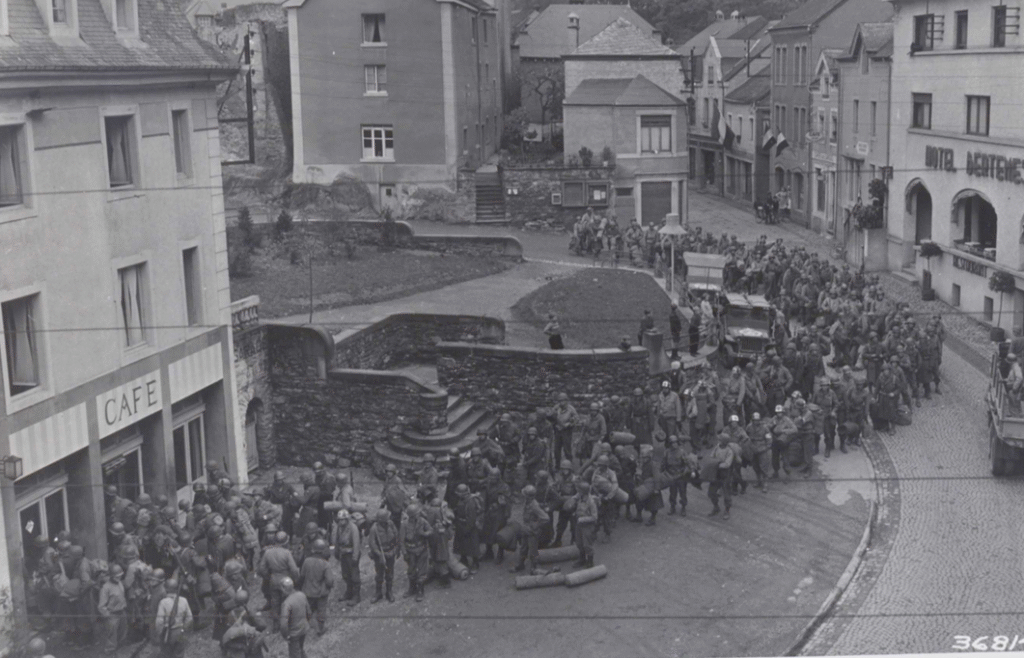

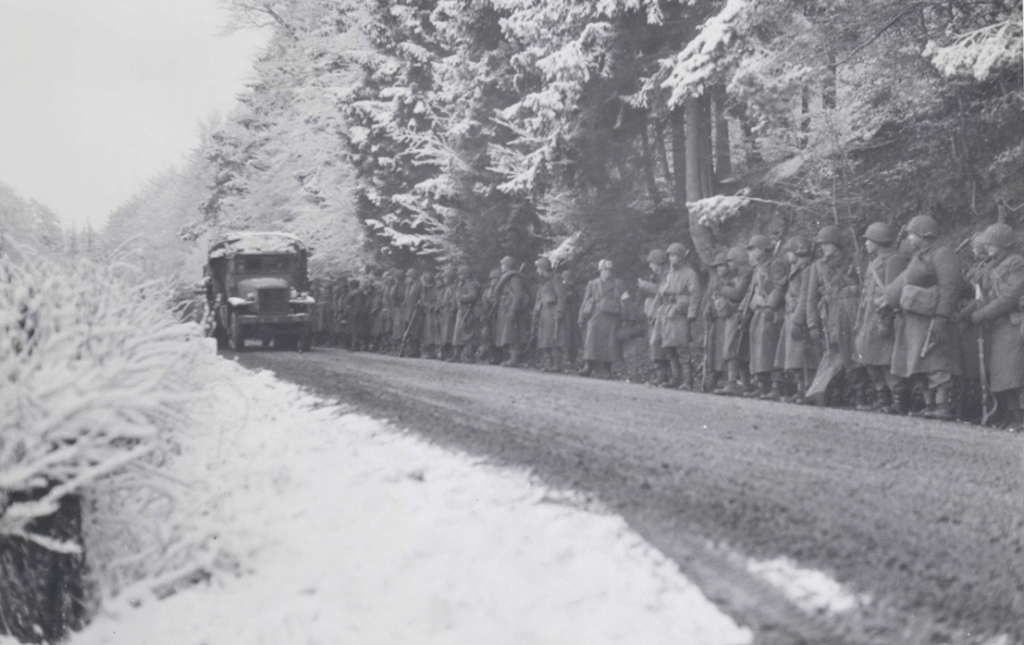

Below are pictures of the initial liberation of Northern Luxembourg by the US army taken by a US Army photographer.

Photo top left: 12 Sep 44. Troisvierges celebrates the liberation as GIs stop to watch. © ANLux FD005-02-023. Right: 22 Oct 44. US Infantary men arrive for a 3 day break in Clervaux, their 1st since July 44. © ANLux FD005-02-024

Photos of the counter offensive or Battle of the Bulge which ran from 16 December 1944 until 25 January 1945. Final three taken by a US army photographer.

Photo top left: German troops passing abandoned US equipment during the counter offensive. © ANLux FD 005-02-034. Right: 20 Dec 44 US troops regroup in defence of Bastogne © ANLux 005-02-37

Photo top left: 22 Dec 44 US soldiers wait for command to advance by foot to reinforce the front line. © ANLux 005-02-040. Right: Early Jan 45 US troops moving up to the front. © ANLux 005-02-50