Pierre visits the World Expo in Brussels in 1958 with his son François.

Carving out a new career

As was customary in many places at the time, the eldest son was expected to inherit the family estate or farm. Pierre knew that, as Nic had inherited the family farm following the death of their father in March 1941, he would need to carve out his own career path. His four and a half years in the resistance had equipped him with vital skills that would be highly valued on any modern CV, such as resourcefulness, quick thinking, results driven, the ability to work well under pressure, and leadership and motivation skills in challenging conditions.

In 1946, Pierre relocated to central Luxembourg to work as a forest ranger for the Water and Forestry Department in the small town of Lintgen, in the district of Mersch. Ambitious and hardworking, he attended evening school and even enrolled in courses in Nancy, northeastern France, which specialized in forestry studies. Soon he would be referred to in documents as an aspiring forest ranger.

In the early 1950s he moved to the Northern town of Wiltz and in the early 1960s settled in the pretty little winemaking town of Remich located on the Mosel river. He worked his way up the ranks to become a chief forestry officer, responsible with his team for all the forests located on the east side of the country.

In the 1970s Pierre was invited to Strasbourg to give a speech on forestry practices. In many ways, he was ahead of his time, advocating for sustainable, green approaches whenever practical, while avoiding the rigidity sometimes associated with modern environmental extremism.

Getting married

In 1950 Pierre met his wife to be Odile Schreiner. Daughter of a landowner and farmer from Godbrange, the Schreiner family had also gone through turbulent times during the war. Arrested for three weeks in July 1942, father Schreiner and the whole family (wife and three children) were among the first fifty families to be deported by the Nazis in September 1942. On 23 September 1942 the national newspaper Luxemburger Wort listed all fifty families with name, address and profession as a warning to others. The reason given for the resettlement was that the families were known in various circles to be unwilling to regard themselves and behave as German minded and German conscious citizens. Through a new work assignment and settlement centre they would be given the opportunity to become a valuable member of the German national community.

By the end of the war, over 1100 Luxembourgish families had been deported to resettlement camps. With barely any notice, they were instructed to pack a small suitcase and report to Hollerich station in Luxembourg City. From there, they were herded onto trains bound eastward, toward an uncertain future, which for most meant a life of hardship and displacement. Simultaneously, the Nazi occupiers confiscated all of their property, stripping them of their homes, belongings, and sense of security.

The Schreiner family’s first destination was Leubus, a forced labour camp located in Lower Silesia (now Lubiąż in present-day southwestern Poland), over 1,000 kilometers from Luxembourg. Housed in the vast and imposing complex of a former Cistercian abbey, Camp Leubus was operated by the SS. It is said that the facility was transformed into a site of secret wartime production with research laboratories and workshops there for the development of radar receivers and also housed armament workshops. Conditions were harsh and the site heavily guarded: deportees endured hard labour, deprivation, and frequent humiliation. Despite this, the prisoners supported one another to maintain morale and hold onto the hope of one day returning home.

Photo left: Departure of families resettled in Silesia. Centre de Documentation et de la recherche sur la Résistance. Photo right: Aerial view of Leubus labour camp 1942. Wikipedia

In January 1943, Camp Leubus was closed as part of a broader Nazi strategy to reorganise forced labour camps for greater wartime efficiency. The Schreiner family, like most of the early deportees to Leubus, was subsequently transferred to Camp Boberstein, roughly 130 kilometers away. It was there, in February 1943, that Pierre carried out his daring and humanitarian mission—delivering over 1,000 kilograms of provisions to the camp. At just 13 years old, Odile Schreiner could never have imagined that, a decade later, she would marry the courageous resistance fighter.

Fortunately, the entire Schreiner family survived their internment and returned to Luxembourg in April 1945, unlike the 21 Luxembourg deportees who tragically lost their lives in Boberstein.

The couple married on 17 October 1953 in Junlingster, eager to begin a new and positive chapter, leaving behind the hardships and turmoil of the war years. In July 1954, they welcomed their son, François born in Wiltz, followed by the birth of their daughter, Jacqueline, in 1961.

Left: Pierre with wife Odile, son François and Odile`s parents Jean-Pierre and Nathalie Schreiner. RIght: Pierre and family, weekend outing in 1959

Keeping in touch

In the post war years, Pierre kept in regular touch with his resistance friends. They had been through so much together, a strong bond united them. He actively took part in the remembrance services held every year in Luxembourg and sometimes abroad in Belgium and France. He took his son François to visit Hinzert concentration camp and told him about how difficult the war had been for many. After the war, Jules Dominique who had recruited Pierre into the Belgian resistance, rose to the rank of major and became chief of the Grand Ducal guard from 1953 to 1966.

The family maintained close ties to Doennange, returning to the farm for traditional celebrations like All Saints’ Day, Christmas, and summer holidays. Summer was also a time for travel. Pierre would take the family across Europe in their car and caravan, with regular stops in France and Belgium. These trips sometimes included visits to old resistance friends in the north and in Draguignan, in southern France.

At home in Remich, Pierre remained active in civic life, organising events such as the May 1st festivities with the town council. Like many at the time, he went hunting several times a year. Odile, his wife, was an excellent cook who more than did justice to the game he brought home, preparing delicious meals for family and friends.

One particularly memorable visit in the early 1960s took Pierre, his son François, and nephew Fernand to the castle of André Peltzer near Spa. A textile industrialist, Peltzer had first hired Pierre in 1936 as a valet, later promoting him to a commercial role after being impressed by his outgoing nature and multilingual abilities. During the visit, Peltzer delighted the boys with a ride around the estate in his convertible sports car. Ever drawn to the outdoors, Pierre pitched a tent in the castle grounds for the boys to have fun and be closer to nature. He later took François to visit Auguste Collart, at his castle in Bettembourg, where the two veterans reminisced about their time in the Luxembourg resistance.

For several years a highlight was the annual visit of their American uncle from New York. Pierre’s uncle Michel had emigrated to the U.S. in the early 1900s, settling in Illinois. Later, son Dagobert, fondly nicknamed by the Luxembourg family after Donald Duck’s uncle, a classic Disney character known for his immense wealth, adventurous spirit, and colorful personality, became a successful lawyer in New York. Each year, “Uncle Dagobert” would arrive with presents, much to the delight of the children, often remote-controlled, a novelty in 1960s Europe. As a teenager, François even spent summers in New York enjoying time with and being spoilt by the transatlantic family.

Pierre also stayed in touch with American servicemen he had met during the war. Invited to visit U.S. air bases in Bitburg and Spangdahlem in Germany in the 1950s and 1960s, he brought his son François along to meet the airmen and see the facilities. Each time a warm welcome awaited them. For several years, Pierre took on the role of delivering Christmas trees from Luxembourg to both bases.

One year, when a large order came in late and was much bigger than expected, Pierre wondered how they would manage to prepare all the trees in time. “No problem,” replied the American airmen. “We’ll come give you a hand.”

Soon after, a large truck pulled up to the Schreiner farm in Godbrange, carrying several Americans equipped with state-of-the-art cutting tools. They got to work immediately—and finished the job in record time.

Decorations for his bravery

After the war, Pierre was awarded the Croix de Guerre (War Cross) and Médaille de l Ordre de la Resistance (Medal of the Order of the Resistance) from Luxembourg. From France, he was awarded the Médaille de la Réconnaissance (French medal of recognition) and the La Médaille des Passeurs. From Belgium, he received the Médaille du Combattant Volontaire de la Guerre 1940–1945 avec deux sabres croisés (Combatant Volunteer Medal with crossed swords), La Médaille des Passeurs Belges and La Médaille Commémorative de la Guerre 1940 – 1945 (Commemorative Medal from the war 1940 – 1945). He was also awarded the Médaille interalliée (Inter-Allied Victory Medal) and a medal from Poland for his humanitarian help. He also received two commendations. One from the USA signed by General Eisenhower and one from the Commonwealth of Nations signed by the Deputy Chief Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force expressing their thanks and appreciation for assisting the escape of allied soldiers and airmen from the enemy.

Photos of medals awarded to Pierre Schon from Luxembourg, Belgium and France.

The lights go out

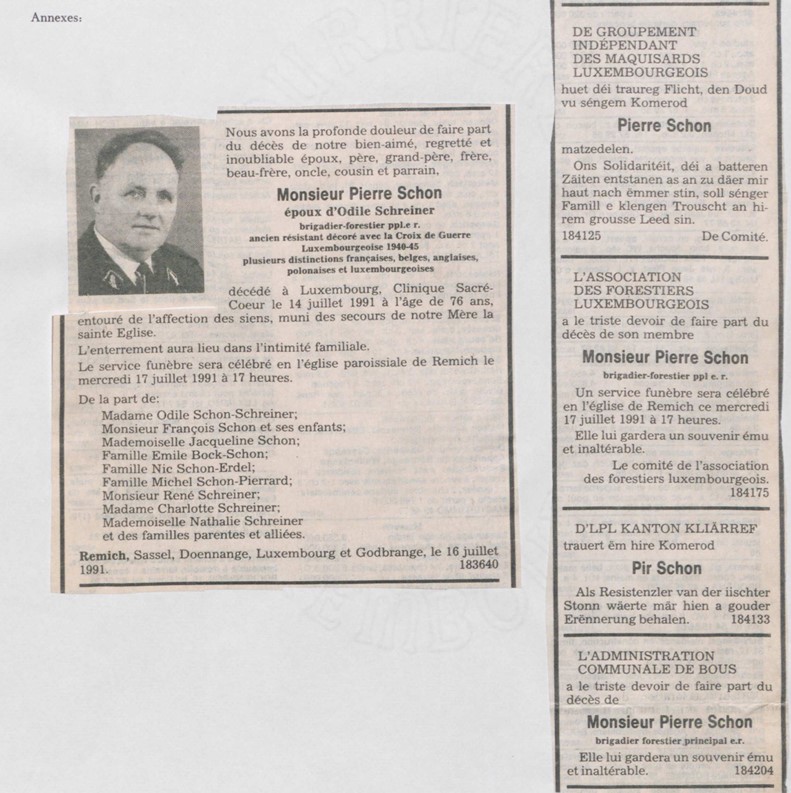

On 14 July 1991, Pierre passed away in hospital in Luxembourg City from heart failure, something that, a decade later, might have been preventable with modern bypass surgery. The tumultuous and stressful war years had likely left a lasting mark on his health. The church in Remich overflowed with family, friends, and members of the resistance, all gathered to bid farewell and pay tribute to a brave patriot and an unusually generous individual.

Pierre was posthumously awarded the Croix de la Résistance (Resistance cross) by Luxembourg in 1991, the most prestigious civilian decoration for resistance activities in Luxembourg during the war.

Hommage to Europe’s brave resistance

Let’s remember the courageous individuals of the resistance across Europe during World War II. These unsung heroes risked everything under brutal Nazi occupation. Working in the shadows with limited resources and under constant threat, they waged a covert war of resilience and defiance. Their often-overlooked sacrifices remain a powerful testament to the pursuit of justice and freedom, efforts vital to the Allied victory and the peace we enjoy today.

According to Livre d’Or des Prisons from the L.P.P.D, more than 10,000 patriotic Luxembourgers were members of the resistance or clandestine organisations. The Luxembourg resistance movements were able to hide 300 political refugees and more than 3,500 young men who had escaped forced conscription into the German army out of 12,080. 350 Luxembourgers fought in the maquis (forest camps) in Belgium and France and 74 of them lost their lives. Over 50 members of the active Luxembourg resistance were executed by the Nazis. A significant number of others died in captivity in concentration camps.

In France, it is estimated that between 300,000 to 500,000 people were involved in the resistance. Around 100,000 were fighters or operatives and hundreds of thousands provided shelter, transport, false papers, food to resisters or distributed propaganda. It is said that between 30,000 to 35,000 French resisters were tortured and executed, killed in action or died in captivity. Another 60,000 to 70,000 of those deported perished in Nazi concentration camps.

In Belgium it is estimated that around 160,000 Belgians were involved in resistance activities. Of these 30,000 were arrested and 16,000 lost their lives; either they were executed or died in captivity.

In the Netherlands around 45,000 to 60,000 people were actively involved in the resistance at some point but only a smaller core (5,000 to 10,000) were consistently and deeply involved in organised, high-risk resistance activities (e.g. sabotage, armed struggle, helping Jews escape). Approximately 2,000 to 2,500 Dutch resistance members were executed by the Nazis during the occupation (1940–1945) while thousands more were arrested, tortured, or deported, and many died in concentration camps.

In Norway, it is estimated that between 30,000 to 40,000 Norwegians were actively involved in resistance activities during the occupation. In total, around 1,900 were killed in connection with resistance activities including executions (around 600), in concentration camps and other reprisals.

In Denmark, estimates suggest around 20,000 Danes were involved in resistance activities with around 400 Danish resistance members killed. Many more were arrested, imprisoned or sent to concentration camps. They successfully helped rescue over 60% of the country’s Jewish population by transporting them across the water to neighboring neutral Sweden, just before they were to be rounded up and deported.

In Poland the resistance was one of the largest and most active underground movements in occupied Europe. Estimates suggest that by the height of its activity, the Polish resistance numbered over 400,000 members, including the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), which was the main resistance organisation. Some estimates indicate that around 100,000 members of the Polish resistance and civilians involved in underground activities were executed or died in concentration camps.

Epilogue

In 1971, my wise old English teacher told us, “You have the freedom to end all freedoms and it is up to you all to make sure this never happens.” It was a profound message, especially for a room full of eleven-year-olds still learning what freedom even meant.

One of the deadliest conflicts in human history, over 70 million people lost their lives during World War II, including 27 million from the Soviet Union. The destruction and suffering caused by the war reshaped nations, altered global power structures, and left deep scars on countless communities around the world.

Learning from the lessons of World War II, we know that totalitarian regimes can quickly seize power if we are not vigilant. Freedom is our most precious gift, and once lost, it is incredibly difficult to regain. Today, Germany stands as a trusted ally, a testament to reconciliation. For the sake of our children, grandchildren, and future generations, it is our responsibility to remain strong, united, and unwavering in our defense of democracy and the way of life we cherish, yet too often take for granted. This commitment begins with remembering our recent history, for only by understanding where we have been can we truly protect where we are going.

A few words from the LPPD and the Amicale LPL

The LPPD (The League of Political Prisoners and Deportees) Asbl was founded in 1946, shortly after the end of the Second World War. Its continuing mission is to preserve the historical records and personal memories of Luxembourg’s political prisoners and deportees.

The association is also in contact with various other groups connected to the Second World War — such as the Amicale LPL — and today also with their descendants, in order to honour the memory and legacy of the Luxembourg Resistance and to promote historical awareness among future generations.

Dear Reader,

Eighty years on from 1945 — the end of the Second World War — one may ask whether it is still necessary to look back on the years from 1940 to 1945. Is there still genuine interest in the past, or is our collective memory beginning to fade?

Let us remember. After the First World War, on January 10, 1920, the League of Nations was founded — intended to protect human rights and prevent future wars. Yet, the security of smaller, and even larger, nations could not be guaranteed.

Let us remember again. On April 18, 1946, following the Second World War, 34 nations dissolved the League of Nations and established the United Nations. It was believed that a lasting bastion had finally been built against authoritarian nationalism.

And today? For decades, peace in Europe was taken for granted — at least until February 2022. Scenarios once thought unimaginable have again become reality. The security framework surrounding us is beginning to fracture. The international order, respect for national sovereignty, and the authority of the United Nations are being called into question. The efforts of democratic parties to contain populism appear to be faltering.

Even if remembrance can sometimes be uncomfortable, it is no excuse to turn away from it. If we focus only on the present and leave the rest to others, we risk losing sight of the lessons of history — in a world where humanity holds the power to destroy itself. Silence leads to forgetting and forgetting erases remembrance.

Here, then, is an opportunity to look back — to the wartime years of 1940 to 1945 — and to the story of Pierre Schon, a member of the Luxembourg Resistance who had the courage to stand up to the Nazi occupier.

But is everything we read about wartime adventures true? Can a story told eighty years after the war still be believed? Historians rightly remind us that we must remain faithful to the facts and resist any temptation to embellish them.

Fortunately, many aspects of Pierre Schon’s story are documented through photographs, and he received numerous distinctions — supported by witnesses who could attest to his actions.

More than ever, remembrance must not fade. To forget would be to cast aside precious experience.

“A nation that forgets its past has no future.” — Winston Churchill

Due to budget limitations, a professional translation of the original story of Pierre Schon into Luxembourgish was not possible. The L.P.P.D. is therefore pleased to have contributed by reviewing the Luxembourgish version — initially machine-translated from English — to ensure that Pierre Schon’s story is also available in Luxembourgish.

Jean Pirsch

President, LPPD

Dear Reader

In times when fear and violence threatened to extinguish humanitarian values entirely, there were always individuals who stood up against inhumanity – unarmed, yet guided by an unwavering belief in the dignity of mankind. One of these individuals was Pierre Schon, a young man from Doennange, to whose life and courage this website and book are dedicated.

As a member of LPL-Rodesch (Lëtzebuerger Patriote Liga), Pierre Schon devoted his strength and determination to helping where the need was greatest. He brought young men safely across the border, smuggled food and messages into resettlement camps, and later joined the Belgian Maquis in the struggle against the Nazi occupiers.

His actions did not stem from a desire for recognition or adventure, but from a deeply rooted sense of justice and solidarity. This website and book tell not only the story of a resistance fighter, but also that of a man who risked his life to save others. It stands as a reminder of the importance of civil courage, the power of solidarity, and the necessity of remaining true to our principles even in the darkest of times.

Pierre Schon was among those who not only cherished freedom, but lived it and defended it. His example reminds us that freedom can never be taken for granted, and that the history of the resistance is, above all, a history of humanity – of those who refuse to look away when our values are at risk.

My heartfelt thanks go to Mrs. Sue Hewitt. Through her dedication and research, she has helped ensure that the story of resistance fighter and LPL member Pierre Schon, her father-in-law, is preserved for generations to come.

Marc Fischbach

President of the Amicale LPL