Header photo Pierre (far right) bringing escapees over the border to Belgium after spending the night in a barn. © L.P.P.D.

Seasoned escape guide and coordinator of safe houses

Between 1941 and 1944, Pierre Schon concealed and safely guided more than 100 people to freedom, Allied airmen shot down over Europe, escaped French prisoners of war, Jews, Luxembourgish deserters forced into the German army, and fellow resistance fighters, many of whom risked severe punishment, even death if captured by the occupying forces

LPL members like Pierre used forest routes to guide people into Belgium. A few people were initially hidden in the large family house and farm in Doennange or in other safe houses he had set up with local resistance members. Others in hideaways he helped built in the forest between Doennange and Weicherdange to lodge escaped French prisoners, deserters and allied parachutists. Then when the time was right, he escorted them during the night through the dense forests and then across the fields into Belgium.

Normally the group would get ready around 10.00 pm and make the crossing around midnight when the German border guards were changing shift. The walk there and back, most of it in the dark, lasted several hours and was approximately 11 kms or 7 miles in each direction.

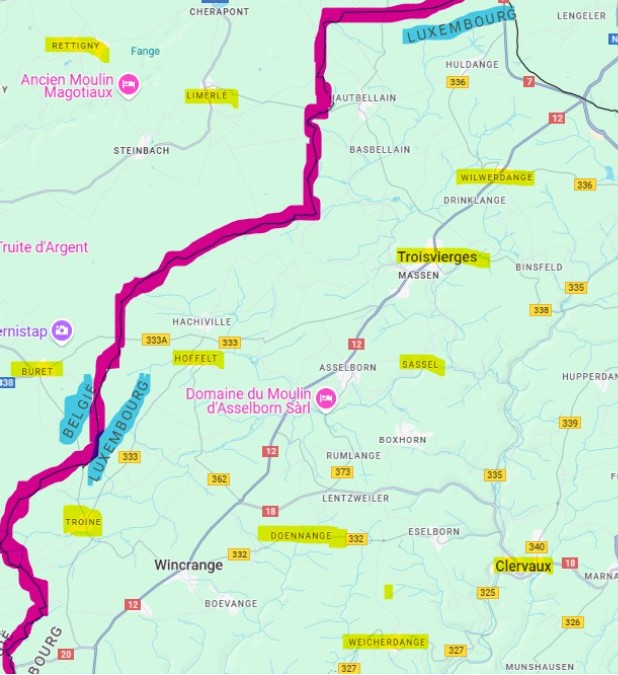

Key villages marked in yellow. Belgo-Luxembourg border in pink

The hideaways were basically underground bunkers or built in the side of a hill, very rudimentary but well camouflaged. In winter they were very cold. Brave locals deposited food in the forest which was collected under the cover of darkness. Sometimes the hideaways had a heavy stove which needed to be transported through the forest to the hiding place to make hot drinks and provide basic heating. Still living on the family farm, Pierre Schon regularly brought food himself to the hideaways.

Photos © Visit Eislek

Working as a team

Pierre worked together with fellow LPL members and escape guides Ernest Delosch and Aloyse Kremer. Their route was via Doennange to Buret and Tavigny, (small villages in Belgium near the border). Their onwards arrival point often Limerlé-Retigny and Bourcy, villages in Belgium with a railway connection, likewise not too far from the frontier.

He set up a series of safe houses in the area near the border to support the people smuggling activities. Among others, he worked with Marie-Louise Didier to hide a number of people in her family house located in Buret in Belgium. Marie-Louise Didier was a member of the Belgian resistance focused on intelligence gathering and the distribution of underground materials.

In July 1943 she was denounced, arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo. During the interrogation the name of her denouncer Jules slipped out. Held in solitary confinement during 4 months and regularly mistreated, she refused to confess that she had harbored escapees. In October 1943, she was deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp, and later transferred to Neu-Brandenburg. There, under brutal conditions, most internees did not survive, forced to work 10 to 12 hours a day in a factory on meagre rations.

With the Red Army advancing just 15 kilometers away, the Nazis forced the internees onto a death march toward another camp. Barely able to stand, she summoned the last of her strength to escape under the cover of darkness. After a brief rest, she made her way to Schwerin, where British forces found her and nursed her back to health. In summer 1945, she was finally repatriated to her home in Belgium.

Helping Jewish deportees

In 1941, the Germans began compiling lists of Jews and intensifying anti-Semitic measures. In October 1941, the German authorities began to deport Jews from Luxembourg. Three hundred were interned in the Camp of Fünfbrunnen (Cinqfontaines in French) close to Troisvierges. Located in a former convent, it served as a transit point prior to subsequent deportation to the larger extermination camps in 1942.

Pierre Schon passed forged ID cards to some of the deportees to help them escape the camp with the intention to hide them and then escort them over the border to Belgium. He also helped provide food for the ones in Fünfbrunnen when rations were reduced by the Nazis as well as diverted food coupons. For most of the time, the camp was not too heavily guarded by the Germans.

During this period, many Jews in Luxembourg went into hiding or fled to neighboring countries to escape arrest. Many contacted the resistance movements for help.

The Polish connection

In February 1943 Pierre Schon carried out probably one of the most daring activities of his time in the resistance.

A humanitarian and growing, like many, increasing concerned about the worsening situation of the Jews and political prisoners, in February 1943 he set off with a truck to Boberstein castle with more than 1000 kg of provisions. He travelled with a forged identity and with a forged authorisation which he would have needed for refueling along the way. Boberstein castle was a Nazi internment and labour camp for resettled Luxembourgers in the Hirschberg valley which is now part of Poland, and housed a couple of hundred people. By early 1943, the internees were becoming hungry having to survive on increasingly meagre rations and in very harsh conditions.

Above photo left: Aerial view of Boberstein castle with outbuildings. Right: Daily life in the camp of Boberstein in Silesia, Centre de Documentation et de Recherche sur la Résistance

At a time when food was strictly monitored, Pierre Schon organised the collection of more than 1,000 kilograms of provisions from the family and neighbouring farms in the Oesling region. With a clear objective and nerves of steel, he transported the supplies across Nazi Germany to Boberstein Castle, a journey of roughly 1,000 kilometers each way. The one-way trip, taking nearly 30 hours and involving numerous checkpoints, was a bold and nearly unimaginable feat.

Two individuals cited by Pierre Schon in archived documentation as witnesses were Auguste Collart, former mayor of Bettembourg and member of parliament, and Jean Peusch, a well-known local politician who served as the DP mayor of Clervaux from 1946 to 1964 and was also a member of parliament. Both men, acquaintances of Pierre Schon, had been deported as political prisoners, along with their families, and were interned at the Boberstein camp at the time of Pierre Schon’s arrival. Auguste Collart was a member of the resistance but the Germans were never able to prove it. A royalist and patriot, moving in aristocratic circles, he donated large sums of money to support resistance activities as well as to assist deportees.

Such a courageous initiative would not have been possible without the discrete assistance of the close-knit farming community around Clervaux, many of whom were involved in the resistance.

After the war in 1946 the Polish government awarded Pierre a medal as a token of gratitude for his humanitarian assistance during the war.

A new identity

The LPL was able to hide and help hundreds from different groups to escape. Meanwhile the people they helped needed to eat so the resistance movement reproduced food ration cards and falsified ID-cards of any kind in order to help people in Luxembourg to survive. Working in a farming community, some food could also be carefully siphoned off to feed those in hiding.

Pierre Schon was able to forge ID cards and had templates as well as original stamps from different municipalities in France and Belgium, which he used as needed. The resistance members were able to also circulate under a false identity to minimise detection. He also worked with his contacts in the Belgian resistance to help produce larger numbers of new identities for those he helped over the border.

In October 1941 the LPL even succeeded in getting weapons out of the police-department of Diekirch (occupied by the Germans).

In October 1941, Nazi Germany attempted to annex Luxembourg through a forced referendum (“Personenstandsaufnahme”). Despite pressure from German occupiers and the VdB, the Luxembourgish resistance launched strong opposition campaigns. Resistance members, including Pierre Schon, smuggled and distributed anti-referendum pamphlets produced by printer Loquet in Brussels sent to them by Alphonse Rodesch. The referendum failed to produce the desired outcome, proving the Luxembourgish population’s firm rejection of Nazi rule. In defiance, they continued speaking Luxembourgish despite the ban and some even tore up their German-issued ID cards as a form of passive resistance.