Header Stock photo Alamy

Being in the resistance anywhere in Nazi occupied Europe was a high risk business. Pierre Schon lost some good friends and comrades during the four and a half years in which the Nazis occupied Luxembourg.

Raymond Petit

In late 1941, facing increased Gestapo surveillance, Raymond Petit who adopted the alias “Fernand Schmitt or AC13 ” went into hiding. He spent part of this time sheltered and hidden by Pierre Schon in the family home. He was an active member and founder of the LPL in Echternach. Despite the risks, Raymond Petit continued his resistance work.

On April 21, 1942, the Gestapo attempted to arrest him in Berdorf. Raymond Petit shot two of the German soldiers and to avoid capture, turned his last bullet on himself, sacrificing his life to protect his comrades and the resistance network. He was just 22 years old.

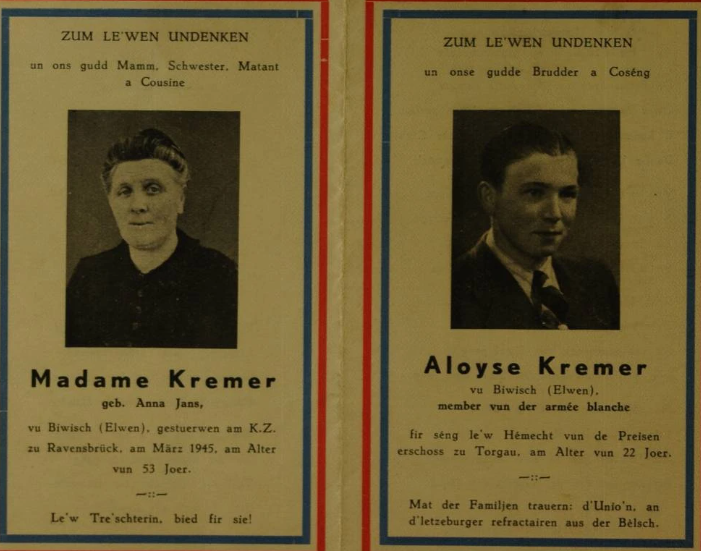

Aloyse Kremer and the Kremer family

Patriotic LPL members Aloyse Kremer and his brother Eugène worked together with Pierre Schon as escape guides to bring a large number of people pursued by the Nazis to Belgium. Photo below shows Pierre Schon and Aloyse Kremer in April 1944 helping escapees on the Belgian side of the border. From left to right Robert Borman, Jany and Norbert Morn, Aloyse Kremer and Pierre Schon.

Photo © L.P.P.D

Four members of the Kremer family from Biwisch, a small village near Troisvierges, were active members of the LPL resistance movement.

Initially from 1941 to 1943 Pierre Schon worked with Aloyse Kremer guiding deserters, French POWs and parachutists from Luxembourg across the heavily guarded border into Belgium.

In late 1943 Aloyse Kremer had to escape to Belgium to avoid being conscripted into the German army. At first he stayed in a safe house and then joined the Belgian Maquis which Pierre Schon had joined nine months earlier following his escape from the Gestapo. Together they continued their escape guide activities from the Belgian side of the border.

Just 3 months after the photo was taken (above), Aloyse returned to Luxembourg in July 1944 to pick up his brother Eugène who had replaced him on the Luxembourg side taking with him 40 ID cards, money and photos for the next group of escapees. In Amperloup Belgium, Aloyse caught the attention of two German border guards who demanded he stop. Thinking of the important information he was carrying he fled. They took aim and he was shot. He continued into a corn field, dropped the bag with the compromising information, continued as far as he could and collapsed.

He was captured and transported to Gestapo headquarters in villa Pauly in Luxembourg City. Thankfully the Germans did not recover the bag he was carrying much to the relief of the network. Despite his gunshot wounds, he withstood the Gestapo interrogations and mistreatment, giving nothing away. He may even have got off with a prison sentence had it not been for a bitter twist of fate.

Six weeks later, two Luxembourger escapee conscripts he had helped over the border and placed as resistance members in a forest camp in Belgium, decided to make their way back to Luxembourg believing the war was nearing an end and longing for home comforts. They were arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo who wanted to know who had initially helped them escape to Belgium. Convinced that Aloyse was no longer alive they gave away his name. Resistance fighters were trained to only give names of people who were already deceased. The Gestapo brought Aloyse in an ambulance for a face to face meeting. The game was up and Aloyse Kremer had to undergo a new trial.

On 1 September 1944, he was sentenced to death. After his wounds had healed, he was transferred to the German fortress in Torgau Saxony ahead of the allied advance and on 19 January 1945 was executed by firing squad just days after his 22nd birthday. Less than one week later, German forces were pushed back for a final time out of Luxembourg and the complete country was liberated.

Aloyse left a farewell note for family and friends shortly before his execution. Written in pencil on the back of a passport photo, the short message was brought back to Luxembourg by a surviving prisoner a few years later: (Source Eugene Kremer, Book Unsägliches Schicksal).

“Dear unforgettable mother, my beloved siblings and family.

Do not weep, I am at home.

They have stolen my innocent life.

If you are still alive, take care.

Up in heaven, we will meet again.

Greetings to all my comrades.

Aloyse Kremer”

The two resistance members were imprisoned and released after the war. What a heavy weight to carry on their conscience, which would probably have haunted them for many years to come.

Mother Anne Kremer was arrested by the Gestapo for her resistance work in August 1944. Severely weakened by the mistreatment suffered at the hands of the Gestapo, she was subsequently deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she perished in March 1945, just a few weeks before the camp was liberated by the Soviet Red Army. She was 53 years old.

Brother Léopold Kremer joined the Luxembourg Armed Forces in 1939. In December 1940, he was taken to Weimar for training as a German policeman. Refusing to swear allegiance to Hitler in 1942, Léon was sent to Dachau concentration camp. He endured the hardships of the camp until its liberation on April 29, 1945 and arrived back in Luxembourg in summer 1945.

Sister Lina Kremer actively participated in the family’s resistance efforts. Following her arrest she was also tortured by the Gestapo. With her mother, she was deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp in August 1944 and transferred in March 1945 to Bergen Belsen. She caught typhus and was rescued at the last minute when the camp was liberated in May by the British. With the help of the Red Cross and in critical condition, she was transported to Sweden, where she had to spend her convalescence in quarantine before finally being repatriated back to Luxembourg. Remembered by all who knew her as a kind, selfless, and generous woman, Lina’s harrowing experiences during the war left lasting damage to her health. Tragically, she passed away at the young age of 39.

Lina Kremer

Brother Eugène Kremer continued his escape guide activities going underground in July 1944 to avoid conscription into the German army where he would undoubtedly have been sent to fight the Red Army on the Eastern front. He survived to see the country liberated in 1945.

The sacrifices made by the Kremer family are commemorated through a monument in their hometown of Biwisch, inaugurated in 1985.

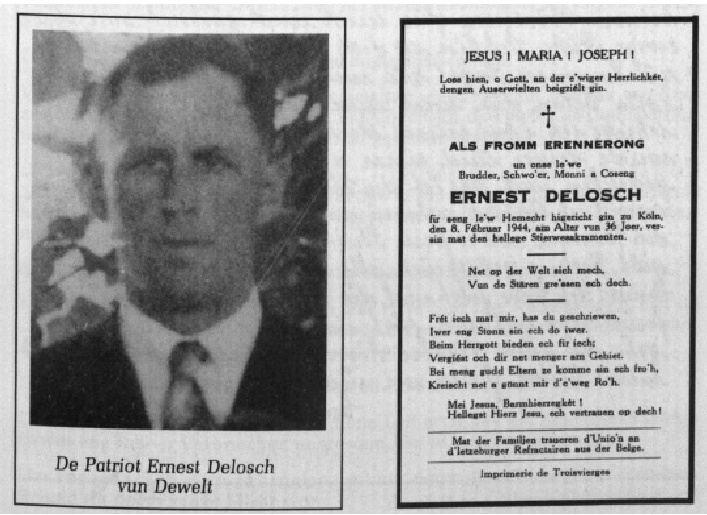

Ernest Delosch

Ernest Delosch, a close friend of Pierre and a key member of his immediate escape guide network, was arrested in July 1943, held in prison in the Grond and brutally interrogated by the Gestapo in Villa Pauly. On 4 February 1944, he was transported to Cologne’s Klingelpütz prison along with Michel Spaus—a seasoned escape guide from the nearby village of Tratten and father of five—and Henri Ameil who was accused of carrying out acts of sabotage against key installations. Just three days later, on 7 February, all three men were sentenced to death. On 8 February, they were executed by guillotine, having been granted the opportunity to write final letters in German to their families. Ernest Delosch was 36 years old; Michel Spaus was 43.

Ernest had apparently been denounced by Jules, a Gestapo informant, posing as a Luxembourger conscripted into the German army who needed help to escape. Probably the same Jules who betrayed Marie-Louise Didier.

Immediately after the war, Jules escaped to visit family in France but upon his return to Luxembourg, a welcome party was waiting and he was arrested and interrogated. Seeing no way out of his predicament, he subsequently committed suicide in prison.

Michel Spaus and his comrades helped approximately 100 forced conscripts and French prisoners of war escape to Belgium. In July 1943, he was arrested and likewise subjected to regular brutal torture by the Gestapo at Villa Pauly. Later that year, in November, his wife and their five young children were deported to a resettlement camp in Silesia, where, fortunately, they all survived. The betrayal that led to Michel’s arrest and eventual execution was later traced to a Nazi informant named Léon D.

According to Néckel Kremer in his book Erennerungen un Deemools, Léon D. was stopped and later interrogated by the Belgian Armée blanche (a group that was part of the Belgian resistance). Apparently, the “interview” did not go well for him, as he was never seen in public again.

Below is a photo of the notorious prison Klingelpütz in Cologne where over 1000 people were executed, including 21 Luxembourgers, during the Nazi period, most by decapitation. It served as a central execution site for resistance members across occupied Western Europe.

Klingelpütz prison Cologne. Photo courtesy of La Féderation des enrolés de force, Luxembourg

Night and fog (Nacht und Nebel – NN) decree

In December 1941 Adolf Hitler introduced the Nacht und Nebel (Night and Fog) decree, a secret Nazi directive aimed to silence and terrorize resistance movements and political prisoners in Nazi-occupied Western Europe, especially in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. The primary objective was psychological warfare: to terrify the population by making people vanish, without trial, execution records, or even grave sites.

The decree was implemented by Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel (High Command of the Wehrmacht) who declared that “Efficient and enduring deterrence can only be achieved by death or by measures which leave the family and the population uncertain about the fate of the offender.” Klingelpütz functioned as a site for the enforcement of the Night and Fog Decree. The bodies of executed prisoners were often sent to anatomical institutes in Cologne, and neighboring cities, preventing burial or identification.

This did not deter the resistance movements; rather, it made their courageous members even more vigilant during the Gestapo crackdowns starting in 1942, acutely aware of the severe consequences they could face, including the risk of deportation for their family members.