Header photo 22 April 1944 Pierre Schon (right) picks up 3 escapees who had been helped across the border to Belgium to take them to a forest camp. L-R Lollo Thines, Ugén Felten and Robert Borman from Troisvierges. © L.P.P.D.

On 3 April 1943 it is not clear who warned Pierre Schon that the Gestapo was on the way to arrest him. Thankfully someone did. With less than 40 kms between Gestapo northern headquarters in Diekirch and the family farm, the Gestapo would have been there is less than one hour navigating the country roads of the time. This gave Pierre very little time to pack the essentials, say goodbye if at all, and take flight through the dense forest towards the Belgium border.

His name appeared on the daily wanted list (Fahndungsliste) of the Gestapo for anti-German activities along with many others who were classified as deserters (Fahndenflucht), all flagged for immediate arrest. With no mobile phone or text messaging in those days, he would have headed to a safe house in Belgium not too far from the border to resource himself and decide what to do next. Safe houses included those of François Bamberg (later imprisoned as a result), Arille Thys the head of the station in Tavigny and Emile Simonis in Rettigny to mention just a few. This was a real gamechanger.

Déjà vu

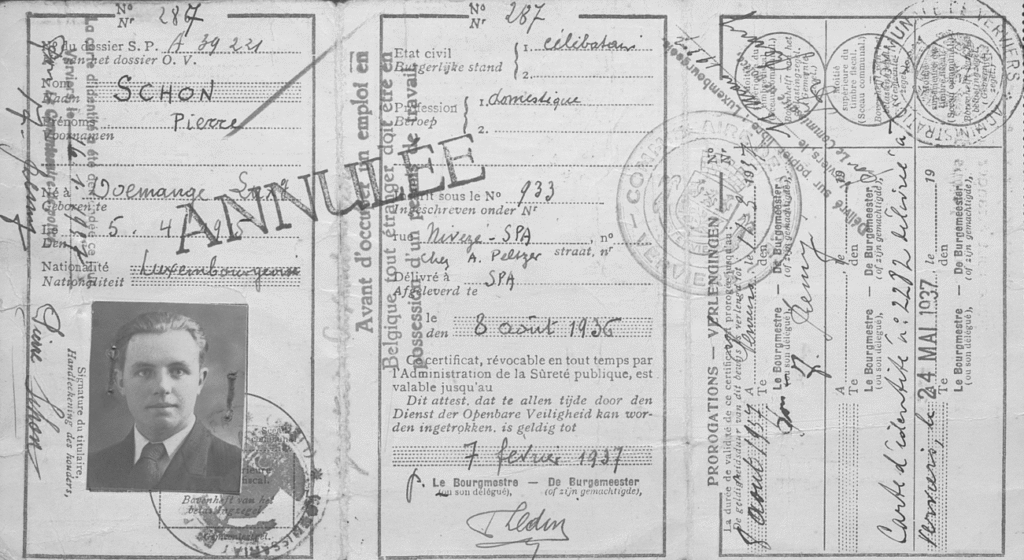

In his early twenties, Pierre left the family farm to work in Belgium, where he was employed by the Peltzer family, leading textile industrialists from Verviers. He served as a domestic helper at their estate, a château located in the Domaine de Nivezé near the town of Spa. As the younger son, Pierre was eager to discover what life beyond the family farm had to offer as the farm was expected to pass to his older brother, Nic. He earned 500 francs a month, along with room and board. Now, a few years later, Pierre found himself back in the Belgian Ardennes, but under very different circumstances.

Photo courtesy of the State Archives of Belgium

The trusted Belgian network

Since 1942 Pierre Schon had built up a trusted network in Belgium made up of families taking enormous risks to help lodge the hundreds of Luxembourg deserters escaping from forced conscription into the German army as well as escaped French POWs. The organisation operated between the Luxembourg Ardennes and the small village of Marloie three kilometres from Marche-en-Famenne. Many of the escapees were brought here by Pierre.

Arriving in Marloie they were handed over to the family of Jean Boever who was also aided by a network of other brave Belgian families. Jean Boever, originally born in Helzen (Hachiville) in the Luxembourg Ardennes near Clervaux and 7 kms from Pierre`s family farm in Doennange, had married a Belgian girl from the Lambert family. He was a livestock trader so very well connected to the numerous farms in the area. The young people were fed, clothed and finally placed on the surrounding farms. The Boever family even used their table cloths to make shirts for the escapees.

Jean Boever – © L.P.P.D.

The organisation was greatly helped by René Nicolay, head of the gendarmerie of Marche. His main task was to procure, before the departure of the deserters, forged identity and work cards. He also helped with food, clothes and money for the escapees. This applied to escaped French prisoners and allied airmen shot down over Europe as well whom Pierre Schon brought along.

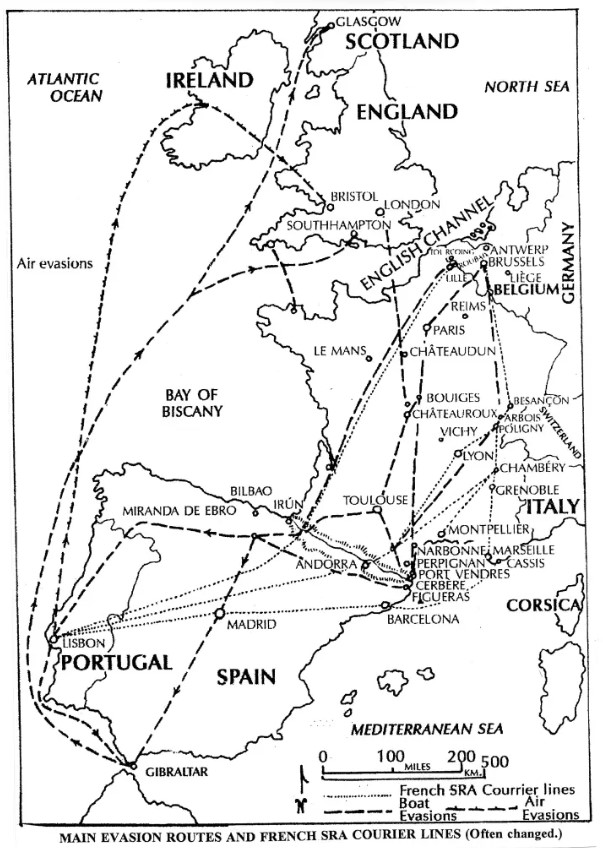

Jews escaping from Luxembourg were hidden in Belgian convents, farms, or safe houses. Some Jews who reached Belgium continued their escape into southern France and Spain, hoping to reach Portugal and sail to the Americas. One of the biggest networks to help them, as well as primarily allied airmen shot down, was the Comet line as well as the Dutch Paris line.

The Maquis

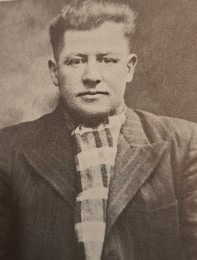

Born in Kayl in 1912, Jules Dominique served as a Lieutenant in the gendarmerie stationed in Diekirch before the outbreak of World War II. In September 1942, his involvement in the general strike against Nazi occupation made him a target of the Gestapo. As a regional leader of the Luxembourgish resistance group LVL, he fled to Belgium, where he joined the Armée Secrète, the Belgian resistance. Initially part of the MNB group, he transferred in January 1943 to Les Insoumis, under whose banner he formed and commanded a unit known as the Armée Blanche du Luxembourg (Luxembourg White Army), also referred to as the Brigade du Lion Rouge (Red Lion Brigade), based in Hompré near Bastogne.

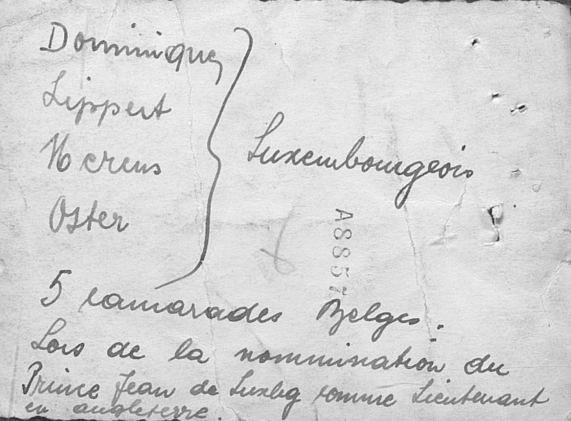

This group, predominantly composed of Luxembourgers, numbered around 120 active members at its peak, including 21 Americans, 9 Russians, and 5 Belgians. Jules Dominique also served as a liaison agent between the MNB section of the Belgian resistance and Luxembourg resistance groups. A charismatic figure, he was widely known by the nickname “Big Gustave.” Recruited by Camille Buysse in January 1943 to form and lead a strike team within Les Insoumis, Dominique also took on the role of recruiter, helping expand the resistance movement’s ranks.

Jules Dominique centre holds a sign ‘The International Council’ to symbolize the international group of 4 Luxembourger and 5 Belgian resistance fighters in the earlier days and on the occasion of the nomination of Hereditary Grand Duke Jean as a Lieutenant in the British Army. Photo © State Archives of Belgium

Shortly after his flight to Belgium, Pierre became an armed member of Les Insoumis. Les Insoumis, translated as ‘defiant’ or ‘unsubmissive’, started out as a clandestine journal and evolved into a resistance movement with 7,000 members. In early 1944, Jules Dominique persuaded Pierre Schon to lead a Maquis unit composed of 20 to 30 maquisards, mostly Luxembourgers who had fled to avoid forced conscription into the German army. The Maquis were rural resistance groups operating in France and neighboring Belgium, living in forest camps hidden deep in the woods to avoid detection. Their missions included sabotaging Nazi infrastructure, gathering intelligence on German troop movements, and supporting Allied operations in preparation for the liberation.

Pierre’s Maquis unit was based in the dense forests near Lavacherie, a village approximately 20 kilometers from Bastogne and 30 kilometers from Marche-en-Famenne. According to Eugéne Kremer who visited the camp, the roof of their hideaway was woven from small fir trees and broom shrubs. They had put together straw matrasses to sleep on. Farmers from the region brought them bread, old milk and some meat. Occasionally they slaughtered a pig or a sheep which they had managed to organise themselves or which they had received from a farmer. The camp was situated a few hundred meters from a Belgian White Army forest camp. Taken by surprise when German forces approached from the opposite side of the forest, the two lookouts were shot and killed. The Belgian resistance fighters had just enough time to flee, abandoning the camp and all their belongings.

The living quarters were underground to avoid detection. When the weather was good the maquisards would eat and spend time outside where they could enjoy natural light. Example of the entrance and inside of the Maquis de Cagna below. Stock photos Alamy.

Home comforts were non-existant as was practically any form of privacy. Three to four inhabitants were constantly on look out duty. Another couple on kitchen duty tasked with feeding the group. Luckily Pierre and his group of maquisards did not have to live in the camp through the extremely cold winter of late 1944 to early 1945 as the east of Belgium was initially liberated in September 1944. Some financial support was extended via Brussels to allow the maquisards to buy food from local sources. When times were tough, the maquisards were not adverse to stealing a few eggs, butter or a bag of flour from a local farm. Many came from a farming background, so they were also apt at setting up traps to catch rabbits and other game to compliment their food supply.

Pierre played a key coordinating role, successfully placing a large number of escapees in various forest camps thanks to his strong ties with the different groups connected to the Belgian resistance.

Acts of sabotage

By May 1944 the Maquis was operational ready for the allied invasion of Normandy which would take place one month later.

Pierre Schon confided after the war that he had been trained in the use of explosives by the British. This would have been the British SOE (Special Operations Executive) who were renowned to work together with the different Maquis in Belgium and France to equip them to be as effective as possible in preparation for the allied invasion and liberation of Europe. The SOE supplied the local resistance with training, explosives, weapons and ammunition, often parachuted into the forest under the cover of darkness. A key supporter of the SOE was the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill who gave the SOE a clear and bold mandate to ‘Set Europe ablaze’. Radio equipment was also provided to establish communication with the Allies. The Maquis used this equipment to send vital intelligence about German movements and to receive orders or requests from the resistance leads, SOE or other Allied forces.

The railway network in the Ardennes was a crucial supply route for the Germans, and disrupting it slowed reinforcements and logistics. Marloie was an important railway junction, and the resistance targeted this station as part of their efforts to disrupt German military logistics, targeting German military supply trains. In the summer of 1944, resistance groups carried out acts of sabotage on the railway lines, including derailing trains and blowing up of bridges and tracks.

First Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum Image: IWM (HU 56936). Second photo © SDL

In his feedback to the Luxembourg National Council of the Resistance Pierre Schon confirmed that he had participated in sabotage activities at Marloie station. He told his son after the war that he had blown up or derailed a few trains as part of his resistance activities. He was also involved in armed combat against German troops.

Other targets he cited were Route de Marche and Route de St. Hubert. Both major roads crossing the Ardennes, these were strategic targets as they were widely used to transport German troops and supplies. Resistance attacks included destroying (mining or blowing up) parts of the roads and attacking German convoys. The German army was much bigger and better armed so the resistance had to rely on the element of surprise, acting quickly and decisively and then retreating even more quickly to avoid detection and capture.

Pierre officially joined the Belgian resistance on 15 May 1943 and served until 14 October 1944 as an ‘armed’ resistance fighter in Les Insoumis, registered under group card number 16485. After the war, Jules Dominique described Pierre to the Office of the Belgian Resistance as ‘the best escape guide of the whole group’ and praised him as an ‘excellent’ resistance fighter who had repeatedly attacked occupying Nazi forces and participated in armed combat. His primary mission was to serve as a ‘troupe de choc’, an assault troop tasked with carrying out direct and often dangerous operations on the frontline against the enemy (derailing trains, destroying roads and attacking German truck convoys, close to the towns of Bande and Amberloup).

A brief overview of several British SOE missions conducted in 1944 in close coordination with the Belgian resistance can be found under the Archives tab, in the UK National Archives section. It is difficult to delve deeper as many records were deliberately destroyed after World War II for security reasons, while others remain classified or heavily redacted to protect intelligence methods, sources, and the identities of agents and resistance members. Working closely together, the SOE and the Belgian resistance became one of the most effective in Western Europe in terms of sabotage and intelligence.

Intelligence gathering

In 1942 the LPL set up a branch in Brussels founded by Charles Diedrich to allow Luxembourgers living in the Belgian capital to join the resistance movement. Diedrich was also a member of intelligence gathering networks Zero and Vic. Alphonse Rodesch, original co-founder of the movement in Clervaux, who was based in Brussels after having had to go underground to avoid arrest by the Gestapo in Luxembourg, also played an important role.

In 1943 and 1944, thanks to the Belgian resistance radio networks Zero and Clarence, the largest collector and transmitter of intelligence gathered by LPL agents, crucial information was successfully relayed to London for the Allied forces. Clarence, one of the most successful MI6 networks in Belgium during WWII, also played a key role in securing official and substantial support for the LPL, both financially and in terms of supplies, enabling them to assist Luxembourg’s escaped conscripts and provide food for the forest camps.

The Zero network maintained radio and courier links with the SOE in London and their operatives on the ground in Belgium as well as with the Belgian and Luxembourg governments-in-exile in London who were based a five minute drive from one another.

Pierre Schon served as an intelligence liaison officer between the maquis which he headed near Lavacherie and the LPL in Brussels. He would take the train to Namur and Brussels relatively often to meet with Alphonse Rodesch. After the D Day landings in June 1944 and advancing of the allied forces, information about German military movements and communication networks would become more important than ever.

The collaboration between these networks exemplified the interconnected nature of resistance efforts across occupied Europe during WWII and especially in supporting the allied invasion and advance in 1944.

Gestapo reprisal against the Schon family

Pierre had always feared that the Gestapo would take reprisals against his family after he went into hiding. In the dead of night on 1 July 1944, that fear materialized. A violent pounding on the door shattered the quiet in Doennange.

“Open up!” shouted a Gestapo officer. The door burst open, and a team of Gestapo agents stormed into the house, heading straight for Pierre’s elder brother, Nic.

“Where is he? Where is he?” the officer barked, shoving a gun into Nic’s back and forcing him from room to room as they ransacked the house.

Nic was arrested and taken to the Grond Prison in Luxembourg City, where he was held from 2 to 25 July. During his detention, he was interrogated and beaten several times at Villa Pauly, the Gestapo’s notorious headquarters. Despite the abuse, Nic managed to convince the Gestapo that he had not seen or heard from Pierre since his disappearance nearly eighteen months earlier.

After more than three weeks in captivity, Nic was released. He narrowly escaped deportation — a reprieve granted because the Schon family had lost their father in March 1941 and relied on Nic to maintain the family farm during a period of severe food shortages.

But the trauma left a lasting impact. When the Germans launched their counteroffensive in December 1944, Nic, along with his young wife and newborn baby, fled to Belgium, painfully aware that he might not survive a second encounter.

Return home

By late November 1944, most of Luxembourg was under Allied control. After one and a half years on the run in Belgium, Pierre Schon returned to the family home in Doennange in September 1944 believing that the war was over.

On 16 December 1944 the Germans launched the battle of the Bulge, a massive counteroffensive through the Ardennes. The Northern and Eastern parts of the country, including Clervaux and surroundings, fell back into German hands.

Luxembourg City and the south of the country were spared a second visit from the Nazis as the allied forces managed to hold off the German advance in the south. However, refugees from surrounding areas added to the number of people in the city. Food shortages and lack of basic resources were common, and people lived under the constant threat of air raids and artillery fire.

Again Pierre was forced to escape from his home in the north to avoid arrest and certain death. Also, if seen, to spare his family from any further Nazi reprisals.

Luxembourg was fully liberated in late January 1945. Pierre finally returned home on 1 February 1945 as soon as it was safe to do so, relinquishing his activity as head of the Belgian Maquis in September 1945.

Gallery

The City of Luxembourg was liberated by Allied forces on September 10, 1944, primarily by General Patton’s Third Army, who entered the city and was enthusiastically and gratefully welcomed by the population after nearly four and a half years of Nazi occupation.

Above left: Citizens welcome Prince Felix on 10 Sep 1944. Photo © ANLux FD 005-02-011. Right: US troops view Luxembourg catherdral. US Army photo. © ANLux FD 005-02-004

Above left: American troops march through the city centre. © Photothèque de la ville de Luxembourg. Author unknown. Right: Crowds gather infront of the city hall. © Photothèque de la ville de Luxembourg. Author unknown.